Culture and Society: Superstitions and Folklore

General

Mexico’s culture is a blend of ancient beliefs, traditions, and Hispanic religious doctrines, resulting in an interesting array of superstitions and practices. Most indigenous communities of Mexico have incorporated into their rites and ceremonies the religious customs brought by the Spaniards in their colonization of the New World almost five hundred years ago. Superstitions seem to involve every aspect of Mexican life, from celebrations, relationships, business ethics and practices, to medicinal remedies.

The native Mexicans were predominantly influenced by the Aztec culture, who dominated central and southern Mexico from the 14th to the 16th centuries. As they grew wealthy and powerful, the Aztec built great cities and developed intricate social, political, and religious organizations. In the Aztec religion, numerous gods ruled over daily life. The earlier Mayan culture attained its peak about the 6th century CE. Mayans developed a complex calendar and practiced astrology and divination. Today, Mayan practices are still observed in many areas. The Mexicans have woven an intricate blend of practices and superstitions from their ancestry and the Catholicism introduced by Spain- a curious meld that often fascinates travelers.

Specific Superstitions

Day of the Dead (Dia de los Muertos)

Honoring the departed through events and special occasions is not exclusively a Mexican practice, but Mexicans have added their special touch to the All Saints’ and All Souls’ holy days celebrated in other predominantly Catholic countries. This Mexican celebration attracts curious travelers worldwide due to Mexicans’ unusual acceptance of the concept of death. Unlike most cultures that view death with gloom and doom, Mexico embraces death with joy. A renowned writer, Octavio Paz, has said that the Mexican is "undaunted by death," and even "chases after it, mocks it, courts it, hugs it, sleeps with it; it is his favorite plaything and his most lasting love."

This unusual attitude towards death stems from ancient beliefs that during this yearly occasion the deceased return to earth to visit loved ones. It is a time for people to recall good memories and to, in some way, spend time with loved ones who have passed away.

Long before the Spanish conquest, the Mexicans celebrated the Feast of the Dead. This feast was held in honor of the Aztec goddess Mictecacihuatl (known as the Lady of the Dead), who is believed to have been sacrificed as an infant. Originally, it was more than a month-long festival celebrated sometime between July and August in the Gregorian calendar (ninth and tenth month in the Aztec solar calendar).

This festival is rooted in the Aztec belief that when a person dies, his soul passes through nine levels before reaching its final destination, Mictlan (the place of the dead). They also believed that a person's soul and its destination were dependent on the type of death rather than the type of life led by that person. How a person died also determined what region they would go to in the afterlife. For example, certain honor was given to those who died during childbirth, in battle, or as a human sacrifice. Mexicans see death not as an end but a beginning of a new and better life in another place.

To accommodate the Roman Catholic beliefs of the Hispanic conquerors, the Feast of the Dead was modified slightly. The date for the celebration was moved to coincide with All Saints’ and All Souls’ Days (November 1 and 2); religious icons were added to the altar for the dead; certain practices contradicting the Christian faith like human sacrifice were abolished; and the concept of purgatory (a place in another dimension where the dead pass through) was integrated into the idea of the afterlife stages of the Aztecs.

November 1 and 2 are now national holidays in Mexico. They are celebrated nationwide and serve as a popular tourist time as well. In most areas, November 1 is set aside for remembering deceased infants and children or angelitos (little angels). November 2 is for those who died as adults. During these days when the dead are believed to visit their loved ones, most Mexicans celebrate by attending mass and visiting the cemetery, leaving flowers and mementos. In rural Mexico, people decorate the gravesites of family members with marigold flowers and candles. They bring toys for dead children and bottles of tequila to adults. They sit on picnic blankets next to gravesites and eat the favorite food of their loved ones.

Mexican offerings on family altars often include a photograph of the deceased family member, surrounded by his or her favorite foods and mementos. Also often represented are the four elements: Earth, represented by recently harvested fruits and vegetables; air, symbolized by tissue paper, flags, balloons, or anything that moves when the wind blows; fire, symbolized by candles (one for each soul remembered, plus an extra flame for a forgotten soul or souls); and water, characterized by a glass or bowl of water.

Other items that appear in the cemeteries or on the altars vary according to personal taste of the deceased or the area’s local custom. Among others, these may include:

- Photographs- to remind people of the deceased and to show visitors who is being honored.

- Personal mementos believed to be recognized by the visiting spirits, thus attracting them and making them feel welcome.

- Icons, statues of saints, crucifixes, or any religious symbols

- Incense- to help the spirits find their way to the altar.

- Marigolds- the popular flower for this event, believed to attract the spirits with its scent.

- Favorite food of the deceased- to rekindle memories and feed the hungry souls who come to visit.

- Actual skeletons, skulls, and bones; folk-art figurines and decorated sugar skulls with the deceased person’s name written on the forehead- these were used in the ancient Aztec era to symbolize life and death.

Each locality in Mexico offers distinct traditions that add a different flavor to this celebration. For example, villages throughout the state of Michoacan reflect the culture of the area's native ancestors- the Purepecha Indians. In most parts of Mexico, floral tributes and feasts in each local cemetery are vital to the two-day celebration. Among the Purepechas, these activities are delegated to women and children only. The male population commemorates the festivity with other rituals related to the fall harvest. In the Island of Janitzio, travelers often trek to the popular graveyard vigils to celebrate this festival.

Tuesday the 13th (Martes Trece)

Unlike countries that harbor negative superstitious beliefs about Friday the 13th, Mexicans dread the 13th day of the month when it falls on a Tuesday. It is believed that the day generally brings bad luck, and thus requires unusual caution. Many Mexicans try not to start a journey or begin any important business transaction on a Tuesday. As a matter of fact, there is a Spanish proverb saying "En Martes ni te cases, ni te embarques, Ni de la casa te apartes," which literally means: "On Tuesday neither be thou married, nor go forth, nor depart from thy house." This superstition, connected with the independent notion that 13 is an unlucky number, resulted in a Latin variation of Friday the 13th.

The superstition of unlucky Tuesdays is also widespread in Greece, Spain, and other Latin American countries. There are a number of assumptions as to the origin of this superstition. Some say that it could have started as a native Mexican superstition. Others say it originated in Spain and was easily adapted by the Mexicans because the capital city of Mexico fell to the Spanish on August 13, 1521, a Tuesday. Thus, it was not hard for Mexicans to believe that Tuesday is indeed unlucky.

Some also suggest that the superstition goes as far back as the 1200s, when the Moors defeated a Spanish king on a Tuesday. Others cite that the superstition is probably linked to the Spanish word for Tuesday, Martes, which was derived from the Roman god of war, Mars, who is associated in folk tradition with death.

The number 13 is considered unlucky in Latin American folklore and linked to Christianity. Based on biblical accounts of the "Last Supper," the 13th man (Judas), who joined Jesus and his disciples, caused Jesus' arrest, suffering, and eventual crucifixion. This led to the belief that it’s unlucky to have 13 people at a dinner table.

Since this particular superstition has a number of variations all over the world and has been associated with various mythologies and religions, its exact origin is quite hard to determine. The Tuesday the 13th superstition is still prevalent among Mexicans, especially among the common people. Even educated people respect practices associated with this superstition.

Susto and Espanto

Susto, literally translated as "right," is a common term in Mexican households. Susto is known as a condition of losing one’s soul through frightening or traumatizing experiences like accidents, witnessing a loved one’s death, or similar tragedies. It is believed that this is an illness manifested by symptoms of nervousness, lack of appetite, diarrhea, and insomnia.

A more severe and potentially fatal version of Susto is called Espanto. Mexicans believe that Espanto is also caused by frightening experiences, but results in more critical consequences. Typically, those afflicted with Espanto were also diagnosed with diabetes mellitus, carcinoma, or liver disease at the time of their death. Extensive studies have been made regarding these conditions, and, although not considered traditional diseases, current psychology categorizes them as a culture-bound condition. The studies conducted regarding this belief have shown its predominant practice in Latino populations in Mexico, Guatemala, and South Texas, with roots from their Indian ancestry. Most areas in Mexico and other Latin countries agree on the causes and symptoms of Susto and Espanto, but the treatments vary among localities. The general treatments are as follows:

- Oral remedies include teas from orange blossom, Brazil wood, rosemary, or marijuana. An oral solution of figs boiled in vinegar is also considered to bring relief.

- A ceremony known as the barrida (sweeping) is also known to cure Susto or Espanto. The barrida should be performed immediately after the traumatic event occurs and is best conducted by a curandero (one endowed with special healing powers sometimes associated with witchcraft) in his home. During the barrida, the patient recounts the details of the frightening experience while lying down on the floor on the axis of a crucifix. Sometimes the curandero lines the crucifix with aluminum foil or other shiny material. Then the patient's body is swept with fresh herbs such as basil, purple sage, rosemary, or rue. On some occasions, an egg may also be used. While the patient’s body is being swept, the curandero and other participants utter ritual prayers in groups of three. The curandero exhorts the frightened soul to return to the body. One session of barrida is usually not enough. This ceremony is usually repeated every third day until the patient recovers. Wednesday and Friday are believed to be the most effective days for barridas. In some localities, the curandero is also known to jump over the patient's body during the ceremony.

Some Mexicans also believe that the person suffering from Susto must go to a graveyard or to a crossroads and take a pinch of dust from four corners of a grave or a highway. Then, he must add to the dust a piece of red ribbon, a gold ring, and a sprig of palm leaf that has been blessed by a priest. From this, a tea mixture is concocted and seven doses are to be swallowed. The tea mixture has an external usefulness also. It is also believed that when poured into a brass kettle that has been heated on high temperature, the sizzling sound would startle the patient and act as an antidote to his shock.

Another known cure for the Susto is for the patient to lie flat on his back with some members of the family wielding an old broom just above the body (this should be done in a lengthwise manner). Meanwhile, the patient should wait with closed eyes while reciting the Lord's Prayer once and the Hail Mary twelve times.

To prevent Susto, one can carry a whole nutmeg, especially when traveling far from home.

Research shows that those who are greatly affected by this condition are "culturally stressed" adults, especially women. There are supposedly Susto/Espanto cases among men and children as well, but it is not as prevalent as among older women. No conclusions have been made regarding these results, although it may be taken as a possibility that older people (women in particular) are more open to this belief.

Mal de Ojo (Evil Eye)

The concept of the Evil Eye is almost a universal superstition. It is known as mal de ojo in Spanish, and Mexicans believe it to be a way of losing one’s soul.

In Mexico, mal de ojo is seen as an illness that stems from the perception that some people are stronger than others and that stronger people have power to harm weaker people. In traditional Mexican and Central American cultures, women, babies, and young children and considered to be weak. Men, as well as rich and politically powerful people of either gender, are thought to be strong. When a strong person stares at a weak one, the strong person can drain the power or soul of the weak one, intentionally or not. Therefore, parents are warned to guard their children, and women are told to be wary when interacting with government officials, rich people, tourists, and men in general.

Some believe that everyone possesses the power to make Ojo (Eye). It is also said that the human eye in general has certain power over people and things. When looking at a person or something with admiration, one must touch what he has admired, or else the person looked at will become sick or the object will break. In Mexico, if a person admires a part of another person’s body, the person who looked must approach the object of admiration regardless of whether the person is a stranger or not. The admirer must then touch that admired part of the other person’s body. This also applies to material things. When someone looks at an object with a sense of admiration or fancy, that person should touch that thing or it will break.

Someone who was looked at with mal de ojo generally shows symptoms of insomnia, diarrhea, vomiting, and/or a fever and bouts of inconsolable tears for no reason. Some common expression derived from this superstition are: "a dirty look," "a withering glance," "if looks could kill," and "to stare with daggers."

Finding the origin of this particular belief is almost impossible, as the concept of the Evil Eye has been found in nearly all cultures. In ancient Rome, professional sorcerers known to possess the Evil Eye were hired to bewitch enemies. Gypsies were also said to possess this unwelcome stare. It has also been a dreaded phenomenon in India and areas in the East. During the Middle Ages, the Evil Eye became widespread among Europeans who feared falling under the influence of an evil glance. During that era, any person with a suspicious look was liable to be burned at the stake.

One of the most commonly accepted theories among folklorists about the origin of this nearly universal superstition involves the phenomenon of pupil reflection. The Latin word pupilla (pupil) literally means "little doll." This is named as such because when one looks at a person, a tiny reflection of the person is seen in the pupil of one’s eye. Folklorists theorize that the early man must have found it rather frightening to see a glimpse of his own image in miniature version in the eyes of other people. He may have believed that an Evil Eye might steal his likeness and that his soul would be trapped in the eye. This notion may be in parallel to the belief of primitive African tribes that to be photographed was to permanently lose one's soul.

In Mexico, it has been observed that the superstition is associated more with children than with adults. Up to this day, the fear of mal de ojo is still widespread among Mexican society’s commoners as well as aristocrats. As a matter of fact, a number of remedies have been formulated over the years to ward off the mal de ojo.Experiences and anecdotes regarding mal de ojo are common topics of Mexican conversations.

In some areas in Mexico, mal de ojo is detected by cracking an egg over the head of the person suspected to be suffering from it; the yolk is poured on a bowl of water. If a small eye forms in the yolk of the egg, then it is affirmative. The next step is to look for the person responsible for the sickness. The offender is said to surely suffer from a terrible headache. Once the offender is found, he must go to the sick person, take a mouthful of water, and from his own mouth transfer it into the mouth of his victim. This remedio (remedy) is believed to be an effective cure. If the sickness persists, there are other prescribed remedies. Whatever the cure, the participation of the offender is essential in the process.

The following are among the common Mexican remedies and practices connected with mal de ojo:

- Chili peppers are known to be effective cleansers for mal de ojo. When a child is thought to have been afflicted by the Evil Eye, the parents spray the child’s face with a mixture of rue (a woody plant with small yellow flowers, native to Europe and Asia). A little aguardiente (liquor, usually brandy) mixed with crushed hot pepper is then rubbed on the patient’s feet.

- Another known cure for the Evil Eye is combination of a small amount of annatto seed mixed with chili peppers. Placed in a cloth bag, this mixture is passed over the afflicted body while making the sign of the cross. The bag should be thrown into a fire afterwards.

- In Coahuila, the person is wiped with ancho chile (a type of chili). The patient’s head is patted; crosses are made over the eyelids and forehead; and the patient is laid down on a bed with arms outstretched in the form of a cross. The chile is then wiped all over the body. The chile wipe is then burned to get rid the negative power absorbed by it.

- In some areas, the help of a curandero or curandera is sought. The curandero/curandera passes an egg over the patient and then breaks it into a bowl of water. The bowl is then covered with a cross made of straw or palm and placed under the patient's head while the patient sleeps. The egg in the bowl is examined in the morning to determine whether or not the cure has been successful.

- Some curanderas treat adults by rubbing the inflamed areas with a mixture of whole eggs, lime, and an ancho chile. The mixture is then thrown into a fire. Due to the fiery nature of chiles, they are believed to absorb occult-like powers. Therefore, it is essential to burn the remnants of the chile and wipe fully to ensure that the negative power does not remain.

Supernatural Beings

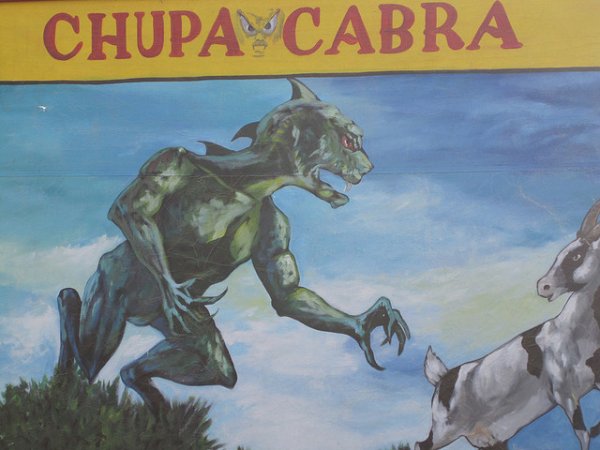

A number of superstitious practices in Mexico are based on their beliefs of certain supernatural, usually evil, beings such as brujas, duendes and chupacabras (goat suckers).

Brujas

Some folklorists believe that the legend of the Brujas came from Europe. Legends describe Brujas as old deformed wicked women who fly on brooms, as popularly depicted in literature and movies. According to the legend, it is believed that the Brujas change into huge birds so they can fly close to houses in the villages. It is also believed that the witches remove their skin before flying, and soak it in a special liquid. People claim to hear the Brujas laughing and singing in a hideous voice while flying and shouting, "Without God nor Santa Maria!"

People believe it wise not to talk about Brujas on Tuesdays or Fridays. Their powers are said to be greater on these days, and it is thought that they can hear what you say about them. Legends have it that witches suck the blood of children, either from their navels or from their big toes. A Bruja will never attack the children of its friends, and they also stay away from twins. The tumbadores (literally translated as the ones who knock down) are said to be the only people that can catch Brujas, since they know certain special orations and rituals to do so. When a Bruja is caught, one must wait until dawn. When the sun rises, the Bruja’s enchantment is broken and only then can its identity be discovered.

Duendes

Duendes or Los Menos, are similar to elves. They are very mischievous little creatures that like to play pranks on people. They are believed to be both good and bad, depending on their mood. They are said to be noisy and bothersome, thus, they are often blamed for any strange noises in the home. They are known to drop stones on roofs and porches, and run, giggle, and laugh loudly. Duendes like to move things or make them disappear to annoy people. If a fire in the fireplace is extinguished, gets too high, or sparks in an unusual manner, the duende is blamed.

Duendes are believed to be no taller than a small boy, but have the face of an old man, usually wear red clothes, and roam around in groups of five. Legends have it that they are invisible to humans, unless they choose to be seen. When they do make themselves visible, it only occurs at dawn or dusk. It is also said that only the children and simple-minded people can see them. When they do, they typically cry.

It is believed that duendes take children, especially boys who are not yet baptized, deep into the mountains or countryside and turn them into duendes. If a baptized child is taken by accident, the duende sets him free in the mountains. When taking unbaptized babies to places like the cemetery, lakes or mountains, extra care must be taken to protect them from being snatched by the duendes who live in those areas. Parents should put a rosary around the infant's neck as an added protection. The children should be kept awake and never placed on the ground.

When leaving these dangerous areas, parents should loudly call their child's name to be sure the child's spirit, and not that of the duende, is in the child's body.

Chupacabra (Goat Sucker)

The chupacabra is a creature that looks like a hunched alien. It is around four feet tall, with big red elongated glowing eyes and grayish skin that is part feather and part fur. It has short arms, with claws for fingers, and legs like a kangaroo. Sharp spikes line the middle of its back. The Chupacabraare known to have supernatural powers, and some say they can fly. Such creatures were believed to be first spotted in Puerto Rico in the mid-1990s, brought by UFOs. Only a few people have claimed to see one, yet there have been many domestic animals (cattle, goats, etc.) found dead with two holes on their neck, blood drained, and their organs sucked out. A few years later, similar cases of animal death took place in Mexico, South Florida, Central America, South America, and in the Dominican Republic. Some people thought it could be a bat-like creature. It is also said that they prey on sleeping people.

Rats

Rats, at the center of many superstitious beliefs, have roots that originate from ancient practices. Rats and mice were believed to posses a keen insight into the character of all members of a household. It is said that rats can sense people with unfavorable attitudes, and they manifest their negative perception of these people by gnawing at their belongings.

Rodents are regarded with a sense of respect- and even fear to a certain degree. Mexicans also say that whoever eats food gnawed by rats will be falsely accused of some wrong-doing.

Other Superstitions

Mexicans are strong believers in luck, and believe that there are certain practices that can invite good luck and drive away bad luck.

- To have a really good day, always put your right foot on the floor first in the morning.

- A pot of fresh basil outside one’s store brings in good or generous customers. A sage plant keeps out irate customers and Brujas.

- For good luck, eat the burned section of a tortilla.

- Never sleep with your back to the door of the bedroom to avoid bad luck.

- Never refuse the food or drinks offered by your hosts or you'll bring very bad luck to the host’s house.

Sneezing

- Say Salud (cheers) when you hear anyone sneeze. A sneeze is a sign that someone is casting a spell on a person. When a person sneezes, it is believed that the person is defenseless and his soul can be snatched away.

Salt

- Salt sprinkled in the doorway of a business increases income and success.

- To bring good luck into the house, dissolve salt in water, dip the mop in the water, and mop from the front door of the house to the back.

- To drive bad luck or spirits from the house, sprinkle salt on the floor and sweep the salt from the back door, through the house, and out through the front door.

Weddings and Marriages

- In Mexico, women believe that if they want to find a boyfriend, they must buy a stamp or statue of San Antonio. After they do so, they need to place it upside down and light a candle in front of that statue or stamp while they say a little prayer. If they do this every day for two weeks, they will finally find a boyfriend.

- If someone sweeps an unmarried woman's shoes, even by accident, she will never marry.

- If a bride wears pearls, she will cry during her married life because pearls signify tears.

- If a bride is pricked by a pin while dressing for her wedding and blood flows, great misfortune in the marriage is expected.

Pregnancy and Child-rearing

- A pregnant woman who goes out of the house during a full moon or lunar eclipse will give birth to a baby with a harelip or with wolf-like features. To avoid this, the woman should carry a bunch of keys around her waist to deflect the moonlight from the baby.

- If the fingernails of an infant are cut before he turns a year old, the child's eyesight will be impaired.

- A pronounced soft spot (fontanel) on an infant's head indicates that ‘”the memory is falling in.”

- When a child loses his first tooth, the parents have to put it under the child’s pillow during the night. It is said that during night, a mouse comes to the child’s bed to take the first tooth and substitute money.

Death

- "Cuando el tecolote canta, el indio muere. Este no es cierto, pero succede." The proverb translates as: "When the screech owl cries, the Indian dies."

- Mexicans believe in death omens such as the howling of an owl or dog, a fallen mirror, or the presence of 13 people at a table. It is also believed that when someone in the house dies and the body does not stiffen quickly, another person will die shortly.

- Another interesting superstition in Mexico considers the way a person dies, or more precisely, the way a murdered person falls down when he dies. It is believed that the person who killed his victim with a sword or dagger will get away if the body falls on its side or back. If the body falls face down, the murderer will surely be captured and put to death. This belief is said to be so widespread among the people of northeastern Mexico, that when the victim falls on his face, the murderer does not even make an effort to escape. In some cases, the murderer voluntarily surrenders to authorities.

New Year

- Eat 12 grapes as the clock strikes 12 midnight on the eve of the New Year. As you eat a grape, make a wish and it will come true.

- Wear red underwear on New Year's Eve for luck in love.

- Get your luggage and take it for a walk around the block if you want to travel in the New Year.

Copyright © 1993—2024 World Trade Press. All rights reserved.

Mexico

Mexico